An overview of the Bible.

Building America and Expanding Narrow Minds with Iron Rails

Building America and Expanding Narrow Minds with Iron Rails – By Daniel Sheridan

#OTD, June 9, 1781, a man was born whose world-changing invention built America.

In the 1830s, the world began progressing technologically at unprecedented levels through the efforts of inventors busily applying their talents for humanity’s sake. One revolutionized travel, helped build America, and expanded narrow minds as a by-product. Here’s the story.

In 1807, Bostonians built the first American railroads, called tramways, which were temporary rail lines designed to transfer loads out of coal mines. Meanwhile, boats and factories utilized steam engines. One day, a clever inventor combined the two technologies.

George Stephenson, an English civil and mechanical engineer, was born June 9, 1781. In 1814, he invented a steam engine running on wheels grooved onto rails dragging attached cars loaded with cargo.

People mocked Stephenson’s contraption. A parliamentary committee man interrogating Stephenson sarcastically asked,

“Suppose, Mr. Stephenson, that a cow were to get in front of your engine moving at full speed, what would happen?”

George, however, unmoved by the little faith cynic, replied with his Northumberland accent,

“It wad be vera bad for the coo!”

In 1821, Stephenson engineered and oversaw the Stockton and Darlington railway construction, becoming the first pubic railway four years later.

Americans adopted Stephenson’s invention by 1830. Within a few years, Americans could travel from New York to Portland, Oregon, at the same time it previously took to go from New York to Portland, Maine, in the days of John Quincy Adams.

Before the railroad, people traveled at a snail’s pace by wagon carrying small loads, which was not easy, especially maneuvering through muddy trails and weather conditions. After Stephenson’s invention appeared in America, freight trains crossed the country through any weather carrying large loads at lightning speeds.

The railroad lowered transportation costs, encouraged travel, and added new cities and states to the American landscape. America became smaller and easier to govern, too.

Furthermore, the railroad expanded people’s minds. Mark Twain said that travel cures bigotry. Efficient transportation exposes people to new worlds and promotes expansive commercial exchanges, bringing people closer and more frequent contact and eliminating bigotry and prejudice from the hearts of the sincere.

In 1830, Americans laid 23 miles of track for horse-drawn cars. By 1840, they embedded 2,800 miles of rail powered by Stephenson’s invention and blanketed over 30,000 miles of the country by 1860. Railroads and steamboats put westward expansion on the fast track.

On this day, June 9, 1781, George Stephenson was born.

The Freedom of the Press

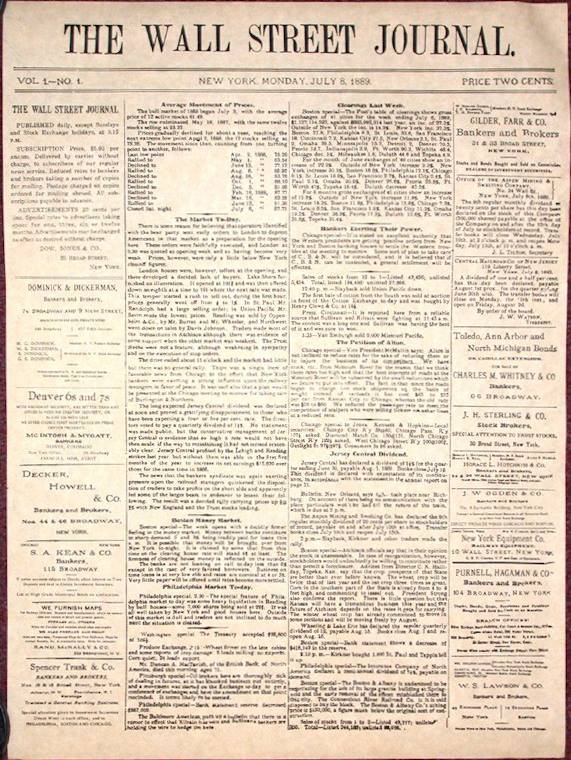

#OTD, July 8, 1889, the “Wall Street Journal” begins publishing.

“Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech or of the press…” #FirstAmendment

Sir William Blackstone said, “Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public.” Freedom of speech is essential in a society, for free debate leads to the correction of public errors. But Blackstone also warned that “if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequences of his temerity.” Freedom of speech comes with responsibilities.

“The only security of all is in a free press. The force of public opinion cannot be resisted when permitted freely to be expressed. The agitation it produces must be submitted to. It is necessary, to keep the waters pure.” –Thomas Jefferson to Lafayette, 1823.

“Our liberty cannot be guarded but by the freedom of the press, nor that be limited without danger of losing it.” –Thomas Jefferson to John Jay

The First Amendment says THE freedom of the press, which was an existing right, and that is why the framers inserted the definite article. What is the press? It includes “all modes of putting facts, views, and opinions before the public.” Because of easy access to information, modern Americans are, in some measure, amateur press members. Think about that whenever you share “information.” What is your motivation? Are you doing it for truth’s sake? Or, are you motivated by party, willing to sell out your conscience for an election victory? If you’re a Christian, are you ready to toss your Bible out the window so you can bear false witness to promote your candidate and issues? When you achieve a victory through vanity, your returns will only be diminished.

Benjamin Franklin provided an example of virtuous news stewardship. He refused to print a vicious article. When the author asked why, “It is highly scurrilous and defamatory,” was Ben’s reply. “But being at a loss, on account of my poverty, whether to reject it or not, I thought I would put it to this issue. At night when my work was done, I bought a twopenny loaf, on which I supped heartily, and then, wrapping myself in my great coat, slept very soundly on the floor until morning, when another loaf and mug of water afforded a pleasant breakfast. Now, sir, since I can live very comfortably in this manner, why should I prostitute my press to personal hatred or party passion for a more luxurious living?”

Captain John Barry: An American-Irish Naval Hero and “Father of the American Navy”

Captain John Barry: An American-Irish Naval Hero and “Father of the American Navy” – By Daniel Sheridan

On June 27, 1963, President John F. Kennedy laid a wreath at the memorial to the Revolutionary War hero, John Barry, of Wexford, on the first full day of his visit to Ireland. Who is John Barry?

The British Navy dominated the seas in the 1770s. During the Revolutionary War, the American Navy was no match for them. But private ship owners bravely filled the gap. Congress granted them the authority to “distress the enemies of the United States by sea or land.” Their pay consisted of war spoils. These patriots sailed up and down the Atlantic, destroying hundreds of enemy ships. Massachusetts and Pennsylvania alone employed about five hundred ships in this service.

Historians have singled out John Paul Jones as the “Father of the American Navy.” However, thousands of other seamen fighting for American Independence were just as patriotic and accomplished as Jones, but Jones got the most press. One man’s story demands our admiration.

Outside Independence Hall in Philadelphia stands the statue of John Barry. Captain Barry, a native of Ireland, was born in Wexford in 1745. When the war for Independence broke out, he willingly offered his services to his adopted country – the new United States. Barry’s exploits were terrific. He cruised up and down both sides of the Atlantic, engaging the British in fierce battles. He lost a few ships and was wounded in action more than once, but he continued to fight and captured many prizes.

The British, unable to beat Barry, tried to seduce their former citizen to switch sides with an offer that most men wouldn’t have the virtue to refuse. They offered Barry $100,000 cash and the command of a frigate in exchange for his loyalty. Think about how much money that was in the 1770s. What would you have done? Here’s what Barry did. He replied without hesitation and indignantly:

“Not the value and command of the whole British fleet can seduce me from the cause of my country!”

Barry was a faithful and virtuous Patriot from the outbreak of the war till its glorious end; he even fought in the last naval battle. His service extended beyond the war, too. Barry helped establish the newly formed government under the Constitution when President George Washington appointed him Captain in the freshly reorganized Navy. He oversaw the construction of the famous frigate “United States” and took command of it when put to sea. Additionally, the Captain defended his country in the naval war with France from 1798 to 1801. He continued to assist his country in other capacities until he was too ill to serve, an illness that took his life.

Captain Barry died on September 13, 1803, in Philadelphia. People said, “Barry was noble in spirit, humane in discipline, discreet and fearless in battle, urbane in his manners, a splendid officer, a good citizen, a devoted Christian, and a true Patriot.”

A Christian Inventor Makes Food Cheaper, Saves Labor, and Donates to Charity

#OTD, June 21, 1834, Cyrus McCormick, a Christian, inventor, and businessman, patents his reaper. He made a fortune, much of it going to charity. His machine saved labor, made food cheaper for everyone, and built the American West. Here’s the story:

Flag Day: The Story of the First Stars and Stripes

Happy #FlagDay! Do you know the story behind the flag?

The Story of the First Stars and Stripes – By Daniel Sheridan

#OTD, June 14, 1777, the Continental Congress authorized the “stars and stripes” flag for the new United States.

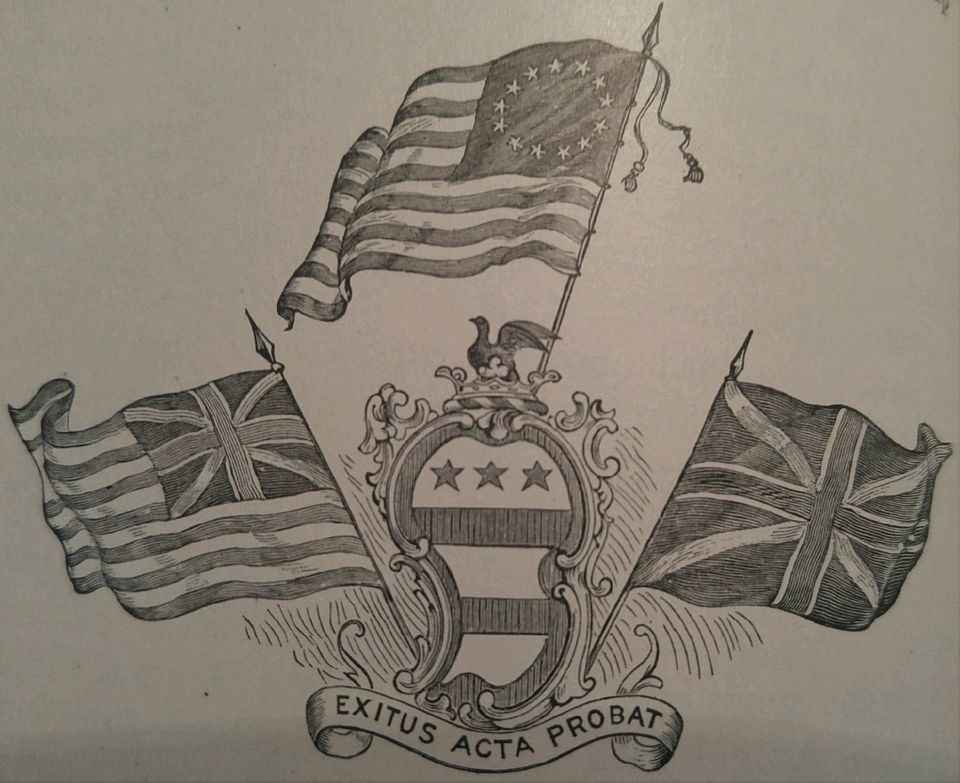

On the right of the provided photo is the British Union Jack with the red cross of St. George and the Scottish white cross of St. Andrew. General George Washington used the flag on the left at Cambridge in January 1776. The flag in the middle, our “stars and stripes,” was adopted by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1777, when Americans exchanged the British Union for a Union of 13 States, symbolized by white stars on a blue background. Below the center flag is the Washington family coat of arms with a Latin phrase meaning, “The event justifies the deed.” The “Stars and Stripes” now represented the United States in their struggle for freedom, and it flew for the first time on August 6, 1777. Here is how that story unfolded.

On August 3, 1777, British Colonel St. Leger, leading an expedition consisting of Loyalists and Indians, laid siege to Fort Stanwix, a log fortification held by two New York Regiments. The American patriot, General Herkimer, knowing the Americans couldn’t hold out for long, raised a militia of 800 men and went to the aid of his fellow patriots.

Herkimer and his band, however, were ambushed Near Oriskany, New York, by the Mohawk chieftain, Joseph Brant. The battle was gruesome. Militia, Royalists, and Mohawks became so intermingled that the fight turned into hand-to-hand combat, men wrestling with bayonets, hatchets, and hunting knives in hand. Many souls fell in the forest “with their left hands clenched in each other’s hair, their right grasping, in a grip of death, the knife plunged in each other’s bosom.” As he lay dying from a mortal wound, General Herkimer continued to encourage and command his men until his last breath.

The battle still raging, men from the American garrison executed a daring move that successfully drove the enemy away. The Patriots, having heard of Herkimer’s fate, returned to the fort with prisoners, spoils of war, and five enemy flags.

The garrison didn’t have a flag when the battle began, but soldiers improvised one on the spot upon their triumphant return. They cut up white shirts to fashion the white stripes, the red from pieces of scarlet cloth sewed together, and the blue background for the stars from a coat. Historian John Fiske describes the scene:

“This rude flag, hastily extemporized out of a white shirt, an old blue jacket, and some strips of red cloth from the petticoat of a soldier’s wife, was the first American flag with stars and stripes that was ever hoisted, and it was first flung to the breeze on the memorable day of Oriskany, August 6, 1777.”

Bancroft says,

“It was the first time that a captured banner floated under the stars and stripes.”

That’s the origin of the American flag.