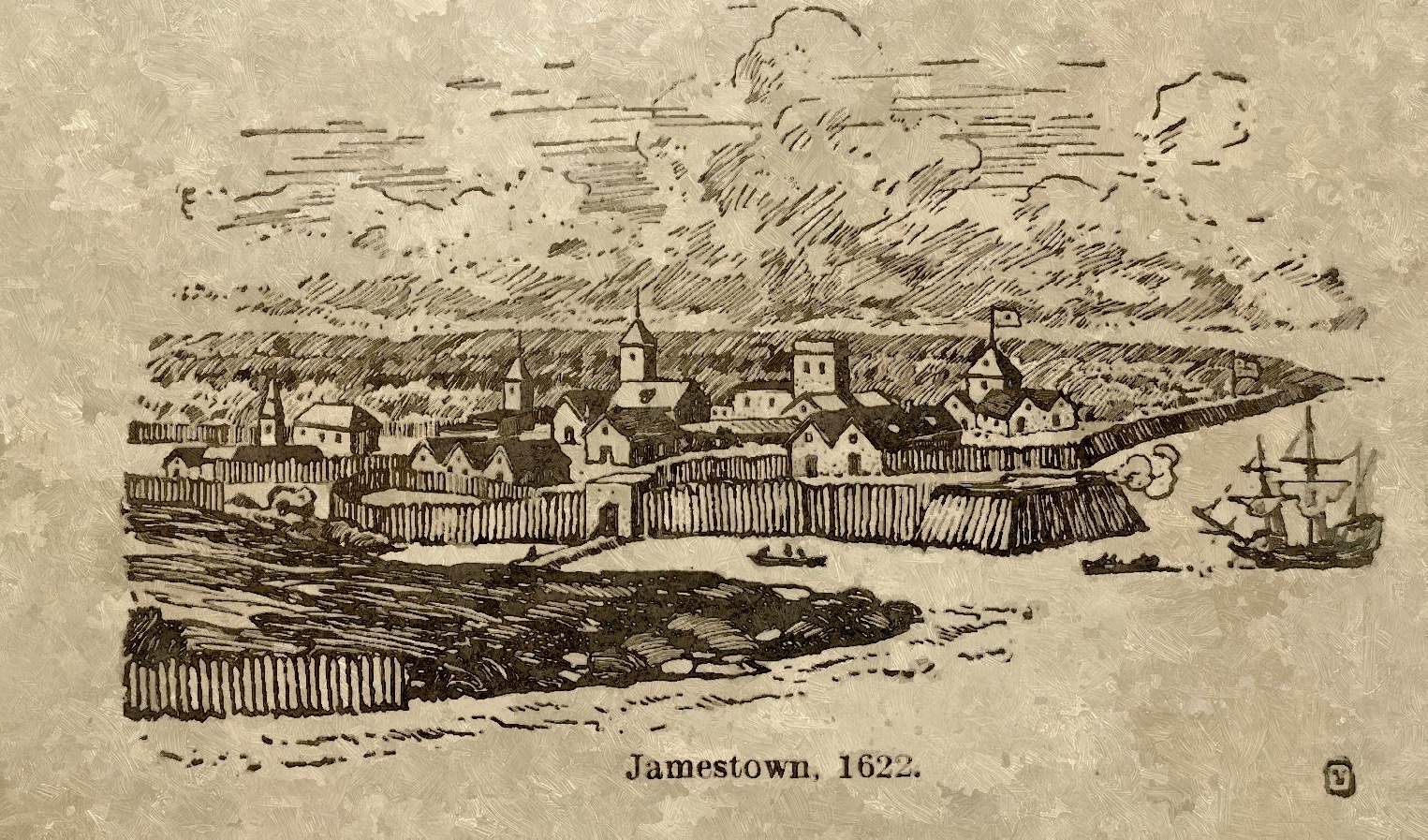

On May 13, 1607, the English colonists landed near the James River in Virginia.

Nations have risen and fallen throughout world history. In the late 1500s, there was another attempt to build a nation. This one was unique. If we could travel back to 1607 Jamestown, the first permanent settlement in America, we wouldn’t notice anything special. Their boats weren’t much better than the ones Columbus sailed on or crossed the Mediterranean 1000 years before that. Their tools weren’t much of an upgrade – their shovels, axes, and hoes were similar to the ones used in ancient China and Egypt; their farming methods were also hoary with age; the same for their clothes and medicines.

At first, it didn’t look like Jamestown would make any progress. Of the first 9,000 settlers, only around 1,000 survived. What made Jamestown unique was its potential. They came from Europe, where Governments controlled economics, politics, and religion. But in the new world, although they imitated those old world bad habits, they were in a position to make improvements.

Economic Improvements

Economically, the early settlers weren’t completely free to develop their talents. Jamestown tried a form of communism, or corporatism, which was a miserable failure. They replaced that system with free enterprise, and things improved.

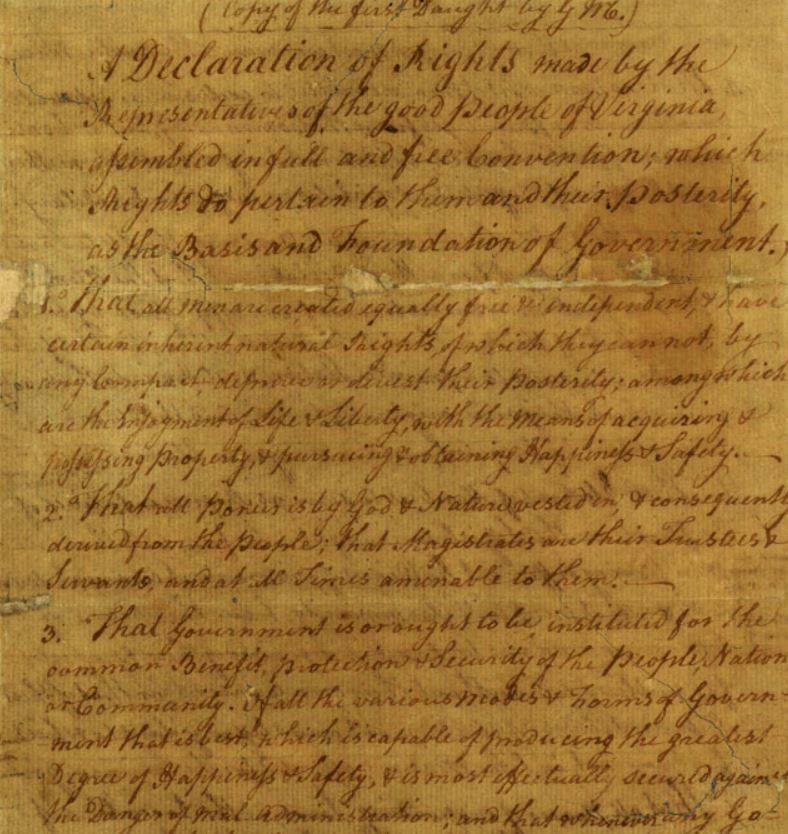

Political Improvements

The colonists also made improvements politically. In the summer of 1619, the first representative assembly in America, where people created laws through their chosen representatives, gathered for the first time, marking the birthday of America’s free institutions.

Religious Improvements

At first, political leaders vigorously controlled religion in Jamestown. But, eventually, over time, Americans would win their freedom in this area too. Thomas Jefferson helped write a bill establishing religious liberty, which he considered one of the most significant accomplishments in his life.

We’ve Come A Long Way

Look how far we’ve advanced economically, politically, and religiously since Jamestown. We went from sailing in the uncomfortable and small Speedwell to enormous luxury Cruise liners, from Monarchy to the Representative Republic, from state-forced religion to freedom to worship.

We may regress if we’re not careful. We are never more than one untaught generation from losing our liberties. Where are we today? Our best days can still be ahead of us as they were for the folks in Jamestown. But we, like them, must work hard to maintain our heritage and pass it on to the next generation.

Our best days can be ahead of us!